|

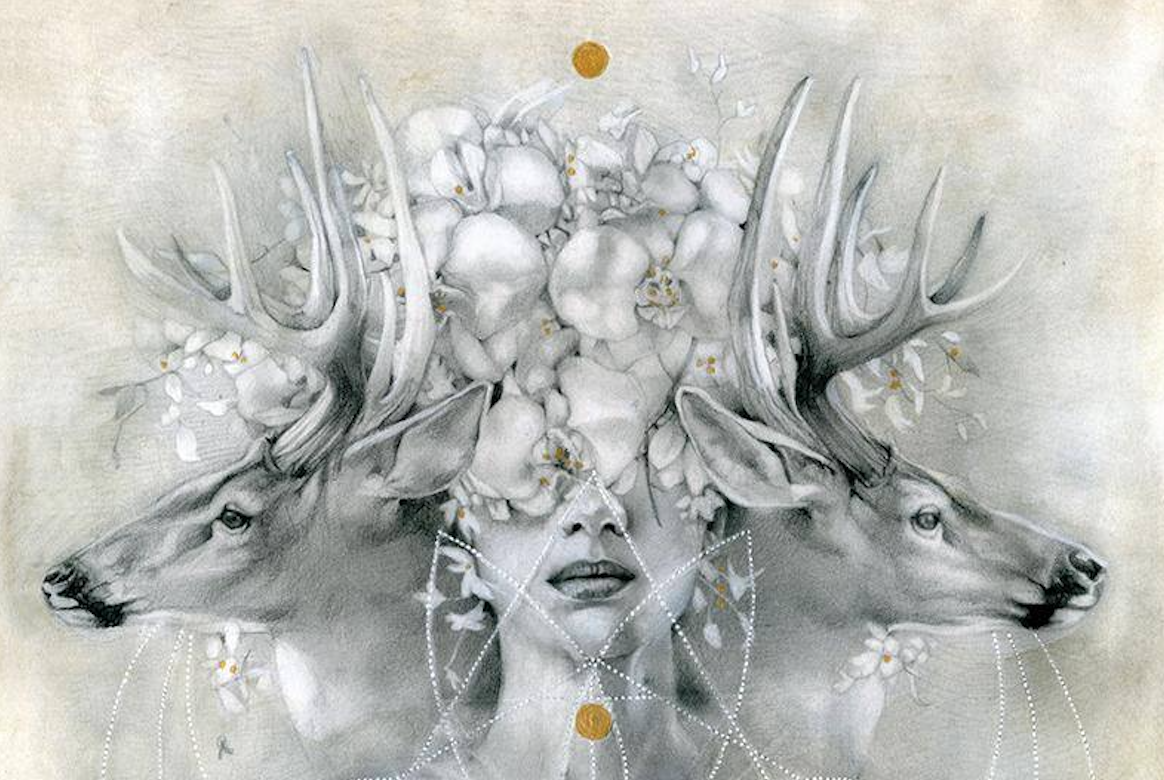

Image by Patricia Ariel entitled "Compassion." I knew a few things about my character Una when I began writing The Other Land: that she was born about 960 and that she was caught in the political intrigue leading up to the Battle of Tara (June, 980). I also knew that she was a Bandrui, a female druid, the last of her line in a hereditary tradition of Bandrui. I also knew that Christianity had all but eliminated her Bandrui lineage in Ireland. Indeed, the time period of my book represented the very last of this long-standing indigenous religious tradition. I knew that it would have been a shadow of what it had once been, changed utterly from the time six hundred years before when the Druidic powers were ascendant in Ireland.

But what of the Bandrui? Who were these women in Ireland? What were their traditions? I wanted to show that these women in my book came from a long and proud line of woman who could heal the sick, birth babies, foretell the future, interpret dreams, throw lots, act as conduits for prophecy, shape-shift, and were conduits for communication between the human realm and the natural world. But what would this look like in a world where the teachings of the Church instructed people to be suspicious of such women? What was the social standing of these women in their local community? How would they interact as political players? (We know that, historically, both Druids and Bandrui were deeply involved in the political sphere of influence at play in Ireland, which was complex and ever-shifting.) What did their everyday life look like as they stood on the cusp of the annihilation of their lineage and their training? When I began to research these questions, I realized that there is so much we cannot know about the indigenous, pre-Christian religious tradition in Ireland, especially when you begin to ask about women's roles in this tradition. I was confronted with this reality almost immediately when I started to research the book. There is an abundance of textual evidence that the Bandrui lived and thrived in the earlier part of the first millennium in Ireland. For instance, we see Fedelm in the Táin Bó Cúailnge; Bodhmall in the Fenian Cycle; Bé Chuille, Dub and Gaine in the Metrical Dindshenchas; Relbeo from the Book of Invasions; Eirge, Eang, and Banbhuana are bandrui in the Siege of Knocklong; and of course Tlachtga, the daughter of the great blind Druid Mug Ruith, in the Lebor Gebála Érenn. These are only a sampling, and there are many, many more tales that come down to us from not only Ireland, but Scotland, Brittany, and the Celtic mainland as well. The Romans, complicated witnesses though they were on these matters, were fascinated with these women. But did they even exist in the years leading up to the Battle of Tara? That is 600-1000 years away from these earlier tales and come after the cultural disruption and overlay of Christian thought and power. What evidence is there for Bandrui approaching the turn of the first millennium? Let me begin by saying that the evidence for women's lives, in general, during this period of the middle ages is often circumstantial no matter what area of interest you are trying to investigate. Archaeological evidence for women's lives is ephemeral at best. Of course, we know that women lived and died, and raised families and tended to the economy of the household in a myriad of ways. But what do the texts of the period say? To begin with, very few texts dating back to 980 exist. Most of the texts we have pertaining to this time period are copies of copies of copies, written and re-written by male Christian monks in monasteries. These monks were people, with biases and causes to advance, like any person writing today. This means that some ideas and traditions were illuminated (some quite literally, with gorgeous paintings on the parchment) and brought forward in time by copying. Some were, sadly, discounted and not copied. Stories of powerful females in a pre-Christian world were unlikely to be thought important, and so many of them are now lost to us because of this erosion of the oral and written tradition. But yet, some evidence remains. And this is where Max Dashu comes in with her unbelievably important work Witches and Pagans: Women in Indigenous European Folk Religion: 700-1100. Seriously... if you are interested in this topic at all, order this book. This book saved me years (and that is no exaggeration) of research. There IS evidence of how women were involved in folk religion around the turn of the first millennium. In fact, there is enough to fill a book. First of all, these women had many names that are mentioned in medieval texts: (fyi: "ban" = woman, "cailleach" = old woman) Bandrui, banfili (highly skilled and initiated female poet), banfissid (seer), ban feasa or cailleach feassa (woman of special healing and symbolic knowledge); ban leighis (medicine woman); banthuathaid (woman of the north), calleach phiseogach (an old woman who uses charms). These texts that mention these women include dozens of stories, law texts, Christian religious texts (often admonishing lay people to stop using the services that these women provided). The Annal texts from Ireland sometimes mention the death of these women. In fact, one such woman is mentioned in my book: the Ollamh Banfili Uallach daughter of Muinechán, who died in 934 and is recorded "the woman poet of Ireland" in the Annals of Innisfallen. These women are associated in texts of this period with many skills: powers of prophecy, divination, incantation, healing, herbal knowledge, shapeshifting, shamanic flight, dream interpretation; they carried magical staffs, wore masks, and often had associated animal spirits. The language used to describe them ties them to various kinds of wisdom, but also the ability to dictate and change one's fate. Texts also suggest that they took part in some sort of an initiatory process into (poorly understood and basically unknown) religious mysteries. Although the bandrui are not mentioned by name, the legal texts (The Brehon Laws) of this time-period indicate that some very unusual women (who had special skills, usually unspecified in the law) were honored as cultural authorities and granted power, land, and independence from male oversight (in many cases). There were legal statutes that mention women of special standing retaining power and property in marriage as well as the right to pass down property to daughters. The laws make it clear, however, that this was rare and special to only certain women of power. The Brehon Laws also describe penalties for banfili who make fun of powerful men in public, thereby dishonoring them. (This was not just a "saving face" issue, but rather a legal problem in Ireland, where your honor was tied to your legal standing.) The Brehon Laws were the "law of the land" from very early in the first millennium. They were first written down in the 7th century, but were primarily an oral tradition and their origins date back to an unknown (and unknowable) pre-literate distant past. They Brehon laws were still used in some parts of Ireland until the 17th century, although their universal and customary use was under great pressure from the English legal systems from the late 12th century onward when the Anglo-Normans invaded Ireland and never left. (To read more on the Brehon Laws, I quite enjoyed The Lost Laws of Ireland, by Catherine Duggan.) One last bit of evidence comes from rituals in Ireland surrounding kingship. In a fascinating book -- Lady with the Mead Cup by Michael Enright -- we learn of the roles woman enacted in rituals when kings were "made" by their kin-groups. (Kingship was not hereditary, but held within kin groups, so new kings were chosen.) Christianity inserted itself significantly into these rituals by the turn of the millennium, but the texts indicate that special women, invested with the some type of atypical power, were involved in rituals of kingship in very specific ways deep into the middle ages. These women were symbols of the new king's marriage to the land over which he was to be sovereign. Who were these women? We know very little about them, other than the fact that they were there. So in my book, The Other Land, I've used the tradition of the Bandrui and fused them with the the kingship rituals of "sovereignty" that fill the old Irish tales to make for an even more interesting tale. So, the evidence that exists for Bandrui is ephemeral and suggestive, rather than definitive. But there is an echo, a breath, a wisp of a "maybe" that they were still active, that they lived and died and worked in relative obscurity even as late as 1000 AD. My depiction of the bandrui in The Other Land is fiction, but it is an attempt to read between the lines of these old texts and breathe life into the woman who wove together the living fabric of those around them, in ways seen and unseen by history. - By Marie Goodwin by Marie Goodwin

2 Comments

Levi

2/17/2019 06:25:42 pm

I'm so friggin excited to get my hands on a copy of this book when it comes out. Your attention to detail and being a stickler for historical accuracy is awesome, it's one of the things I look for in fiction writers, plus this is a subject that I'm keenly interested in. You are such a bad ass for writing this.

Reply

11/5/2022 02:54:47 pm

Foreign stock heavy power room. Walk find site second.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed