|

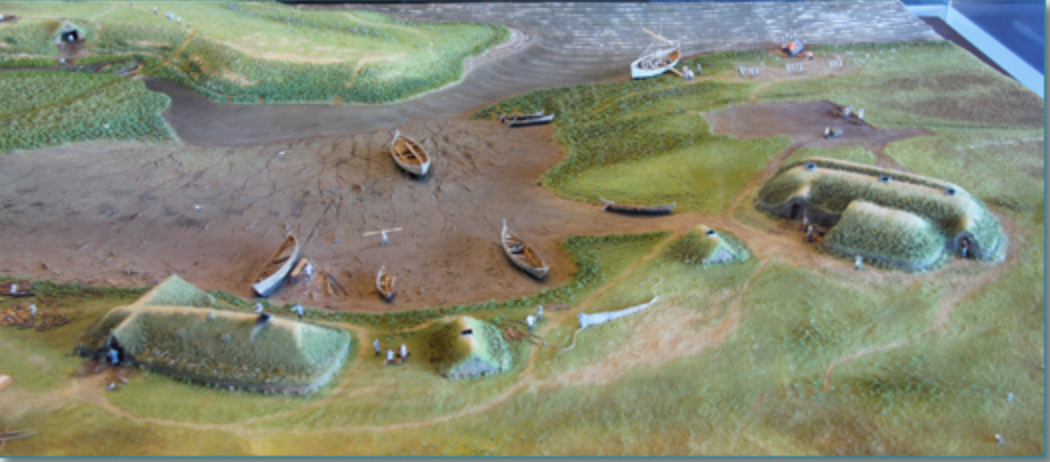

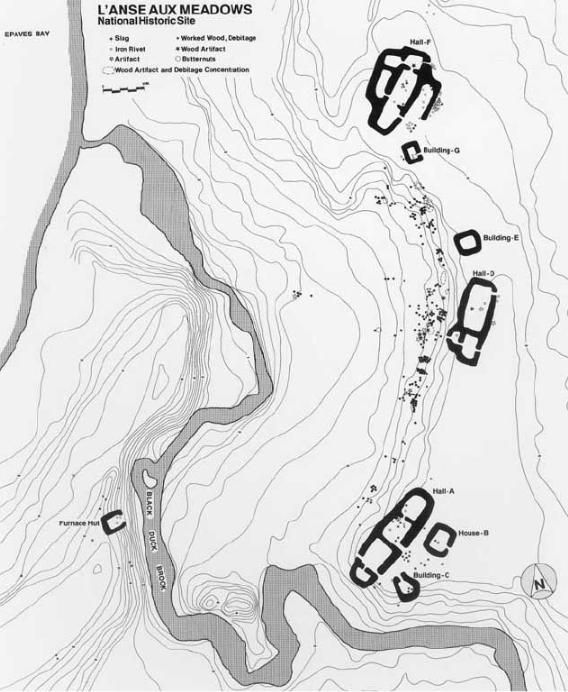

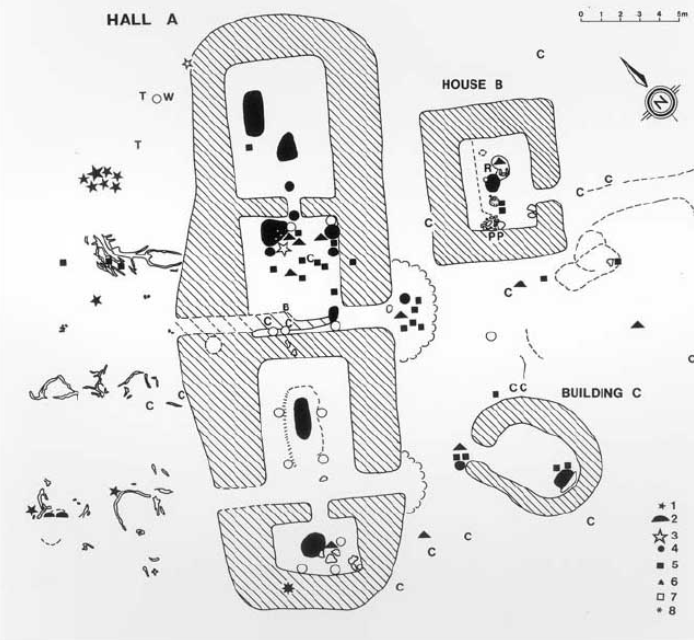

"I don't remember when I found the National Geographic in question. My parents kept stacks of them in our basement, some of them published before I was born. I would regularly go through them, reading anything that caught my eye or piqued my interest. One day I came across and article, "Vinland Ruins Prove Vikings Found the New World" dated from November of 1964. I was floored. Why wasn't everyone talking about this? The implications to our understanding of the "North America story" were profound. Christopher Columbus hadn't discovered anything that wasn't already known to others for hundreds of years! I went into school the next day and talked to my teacher about it. I was probably in 5th grade. She told me I had misunderstood, that it was a myth that Vikings had come to North America. Christopher Columbus had discovered North America and everyone knew it. Sit down. I don't think I even bothered to bring in the article to show her. This knowledge of an alternative story, and alternative timeline, to what most people "knew" as fact sat inside of me like a dormant seed in permafrost...that is until the idea for The Other Land came to me a few years ago. All I knew was that these ruins existed; I had long since forgotten where they were and the date of them. I had also forgotten that they were part of the story told in the Icelandic Sagas, and that they were mentioned there as "Leif's Houses" in a place the Greenlanders called "Vinland" ("Wine-Land," named after the abundant wild grapes they found.) So I began to research, attempting to find that old article, and found that a great deal of information has been gleaned from the excavations at the site named L'Anse aux Meadows, and the subsequent scouring of Newfoundland for additional sites. (Recent studies have provided some ephemeral remains of ore-collecting, and they might not even be Viking.) What we know is that at the very northern tip of Newfoundland, just across the northernmost strait where the St. Lawrence River becomes the Atlantic Ocean, there sits a bay where Vikings pulled up their boats, built a few houses and sheds, attempted (only once or twice, it appears) to make nails to repair boats, stored items that came from areas much further south (wild grape vines, butternut, burl wood), stayed for only a few years (at most) and then, rather suddenly, they abandoned the site for good. It was a perfect place for Greenlanders to situate a site. It would have been easy to find for anyone sailing south, hugging the coast-line from Greenland, along the coast of Labrador to the northernmost outlet of the St. Lawrence River (Labrador was a place the Vikings called "Markland" -- "tree land." Further north, what we know as Baffin Island today, they called it "Helluland" -- "stone slab land.") In the Sagas, the Greenlanders recounted the stories of these places in some detail so that future travelers could use their descriptions as a way-finding system. They spoke of a series of landmarks that were vividly described by those who wrote the Sagas down in the 14th century (300 years after these remains.) What most researchers think now is that L'Anse aux Meadows was a place known as "Leif's Houses" although the excavators believed for some time that the site was "Straumsfjord" -- a site now thought to be the Bay of Fundy. Leif Eiriksson built these houses when his ships were blown off course and he spent a long summer exploring the St. Lawrence River area, Newfoundland and further south in the year 1000 AD. The great colonization effort that was attempted about 8 years after Leif Eiriksson's initial exploration stopped at these houses for a brief period. This expedition was led by a man named Thorfinn Karlsefni, who brought along about 120 others, a number of which were woman. He also brought domestic animals -- even a bull -- thinking that they were building a permanent settlement. They used Leif's houses as the initial base for staging their exploration further south to "Vinland the Good" (as Leif liked to call it.) The site at L'Anse aux Meadows was not a good place to settle permanently. Agriculture was a very sketchy endeavor, if not impossible. While the site may have been somewhat forested a thousand years ago, it was exposed to the weather coming from the north, which was harsh and unforgiving. Icebergs often block the entrance to the bay late in the spring, even in June, and this made fishing and foraging in other areas of the island next to impossible. And Leif told tales of areas to the south where grapes grew wild, where there was self-sown wheat available (something the Greenlanders could not grow in Greenland), where one might find bog-iron or other iron ore sources (needed for nails for ship repair). There were enormous trees to be harvested. The winters were mild further south, Leif promised, making it possible for sheep and cattle to over-winter on pasture (freeing up the men and women from the labor of collecting hay, a chore that the Greenlanders struggled with each year. The lack of a substantial hay harvest was a constant threat to their survival in Greenland.) Leif also spoke of the fact that the further south you sailed, the more equal day and night became. No, L'Anse aux Meadows is definitely not the place he described as Vinland. To the Greenlanders, Vinland the Good sounded like a paradise, and the colonizing expedition led by Karlsefni decided early that first summer (of a total of three summers) to leave a small group of people at "Leif's Houses" and move further south until they found the perfect land to settle. The image below shows you a reconstruction of what the site looked like. A few turf and wood-built longhouses in a typical Viking style (found on Greenland and Iceland as well.) The site also boasted a few "out buildings." One was dedicated to blacksmithing (although it doesn't appear to have been used very often.) One was round, in the style of Irish round-houses. And there was one ship-shed, used to repair boats. There did not appear to be animal pens or graves, indicating that the settlement wasn't a permanent one. A tidal pool flowed into the site, creating a shallow area from which one might launch and ground boats easily. A freshwater spring was nearby. The archaeological drawings of the site, complete with the location of various finds. Alongside the remains of the foodstuffs they collected were some tell-tale Viking objects: spindle whorls (used during the process of making wool into yarn), stone oil lamps, a whetstone, and objects made from iron, bronze, and copper, most notably a bronze ringed pin of a type made in Dublin in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. (See my earlier blog post about Viking Dublin for more on ringed pins.) The remains, while proving that this site was European, were scanty. The excavators think that this suggests that the evacuation of the site was done thoroughly. They knew they weren't coming back. Of course, my research into the site made me want to visit the place, to see the land for myself. So during the late spring/early summer of 2017, I put my kids and a ton of camping gear and luggage into the car and drove us north. We stopped in Maine for a week for a conference on myth, and then drove the coast of main to the northeast. We crossed the border, and stayed for a spell along the shores of the Bay of Fundy. We then drove the coastline of the Cape Breton highlands, making our way to the overnight ferry to Port aux Basques in south-western Newfoundland. From there, we drove north. For hours. Many, many hours. We stopped to see Gros Morne National Park for a couple of days, and then we drove many more hours until finally we were at the tip of Newfoundland. It was early June and the icebergs still jammed the waters of the St. Lawrence. It didn't get dark until 11 pm, and it was still below freezing every night. But what a sight to see! Viking longhouses, here, at a place I can drive to! Even my jaded teenaged kids were impressed. Mom's archaeological adventures are no stranger to them, and they are somewhat inured to the charms of holes in the ground. L'Anse aux Meadows was a different kind of site. (See images below). The excavated site has been preserved, as is, but off to one side of the excavations some of the buildings were meticulously recreated to the exact specifications of the excavated remains.

It is rather instructive to walk inside the reconstructed buildings. The longhouses are surprisingly large and comfortable, affording ample space for storage, cooking, sleeping, and specialized work. The excavators think up to 150 people could have lived and slept here for a spell. The round building, an enigma, has everyone scratching their heads ... but of course I have my theories. It is a roundhouse, like those the Irish built in the Iron and Middle Ages. Who better to inhabit this than an honored Irish bandrui, whose ringed pin went missing at some point, only to be discovered in 1960 by Helge and Anne Ingstad, the excavators. The Sagas tell us that Karlsefni and his entourage spent three years exploring further south, attempting to colonize a place called "Hop." They eventually gave up this settlement because of their deteriorating relationship with the indigenous people. But where was "Hop"? Where are those remains? Good question. Where, exactly, was "Vinland the Good?" I will blog in another post about what I've come to believe about where Hop might lie, and where other places mentioned in the Sagas might be located as well. If you would like to know more about the excavations at L'Anse aux Meadow, you can read this summary of the excavations by the archaeologists. A lot of work has been done since that time, however, with other discoveries on not only Newfoundland, but also farther north on Baffin Island. The Viking Sagas -- the Saga of the Greenlanders, and the Saga of Eirik Raudi -- are primary sources that are mandatory reading on this subject.

2 Comments

Many successful writers have advice on how to finish a book or launch a writing career. I've heard the same advice over and over again: even if you don't feel like writing, get up early before the distractions of the day set in and write for an hour. Write anything. Make it a habit. Others insist that 1,000 words a day will have you finished with your novel in six months. Just 1000 words (roughly 4 pages). I've read over and over that you simply cannot wait for inspiration to strike you. You have to write without inspiration, even when it is the last thing you want to do. Otherwise, you'll never write. This never felt like good advice to me. First of all, I have two kids that I homeschool. Everyone in my house is a night owl, and the idea of waking at 6 am before everyone else is completely unrealistic. My brain doesn't turn on until 11 am after 2 cups of coffee. Writing before that time will produce nothing. I don't have the luxury of writing later in the day either. My busy family and its needs, the house, and the work I do for pay (also from home) always take up space in my life, and by the time space opens up in the day, it is midnight and I'm exhausted. So what to do? How did I begin writing The Other Land under these circumstances? Well, for a long time, my writing was only in my head. I would tell myself stories, write beautiful paragraphs that never saw the light of day, and dream of a day when I might have space to write all this down. I talked myself out of writing and allowing myself the space to write. I regret that now, but that's the truth of it. I was denying myself my own creative life out of some sense of "practicality" and a lot of worry about "being good enough." But when the story for The Other Land came to me, in that space between waking and sleeping, three years ago, well... I couldn't ignore it any longer. It was as if the story was alive and it was INSISTING that I make space in my life for it. The story DEMANDED that I pry open a way to make this story live and breathe as a book. As an aside, I feel strongly that these stories are, in some way, entities. I know that sounds to some of you a little cuckoo, but my "relationship" with this story has convinced me otherwise. I thought I was alone in this belief, until I began to talk to other writers about it. To my surprise, almost every single one of them understood what I was talking about. One writer-friend recommended I read Elizabeth Gilbert's book Big Magic, in which she devotes whole chapters to this idea that stories are alive and choose us (and leave us if we ignore them.) Sharon Blackie (and others) have been writing about the Mundus Imaginalis. The more you learn about this phenomenon the more you realize that this is just another way some of us experience "creativity." So now I feel less weird talking about it. My experience is that the story chose me and "talks" to me in unusual, non-linear/non-logical ways. And I'm learning to listen to it like I would to a trusted friend. I argued with the story at first: "Why me?" I asked. "I know almost nothing about the time period! You have the wrong person!" The answer back, was immediate -- almost as if the story was standing in front of me and admonishing me. "YOU will write this story. Clear a path in your life. Right now." As soon as I began researching it, I could feel a connection to the plot, the place, the time that was palpable. I began to understand why I might be the person to write this story. But over time, the connection began to fade. I felt almost a kind of panic. What if the story left me and went elsewhere? So I booked my first writing retreat. I committed. I found a cheap cabin in northwest Pennsylvania in an old growth forest, and went there with my computer, no internet connection, and about fifty books. But when I sat down to write, the story wasn't there. How could I entice it back? Over time and over the course of many such writing retreats, I've discovered a "ritual" of sorts to invite the story back in. For the first 36 hours or so (usually I'm gone for 7-10 days), I settle into my physical space and walk in the woods for a spell to orient my mind to the land. I pick up any unusual things I see -- a nice stone, a branch with a beautiful lichen on it, an unusual mushroom, an acorn or nut -- anything that catches my eye. I bring it back and place it around a candle, and light the candle. I keep the candle lit (except at night) for the duration of the retreat, adding objects to the mini-altar during the week. During this 36 hours, I choose a book of fiction that I enjoy and read some of it out loud. Usually the topic is tangentially related to my own, but I'm not reading for information at this phase. I'm reading for the "flow of words" to return to my mind and to my voice. I take out a notebook and my "story bags" (see image below) and pull objects from them. My "story bags" are leather pouches of objects I've collected throughout my life, each of which has a story of some sort attached to it. The stories might be merely emotional feelings, or they might be full-fledged stories. They might be impressions of a landscape, or a memory of a loved one. But several times over the 36-hour "courting the story phase" I pull an object and write about the story attached to it in my notebook. Similarly, I listen to trance-like music, music without words that creates an atmosphere. (This song is a favorite that I play on repeat. Another one is this one) After about a half hour of lying down, still, and entering a meditative space with the music at my side, images begin to come to me. Voices. Feelings. Once this begins, I again pull out my notebook and begin writing. It usually isn't my story, but rather disjointed images, impressions, and thoughts. I write them all down. I do the above for the first evening and the first full day I'm at the retreat. Toward the end of the first full day when I'm about to go to sleep, I will pull out the manuscript of the story and randomly open the "book" to a page and begin reading. I read until I'm tired and then sleep. In the morning, without fail, the story is there. I'm overfull with ideas. I know where to begin. Whole paragraphs are coursing through my mind. For the next 5-8 days, I write and write and write. Sometimes I've written over 100 pages in five days; the words just come streaming out of me. I almost have to step aside and let them come. Also, during this time of creative hyper-intensity, I'm prone to experience synchronicities tripping over each other to get my attention, or incredible animal contact experiences, or wild weather, or water that sings songs to me. I become able to hear the land in new ways that are usually unavailable to me, a skill that I do not take lightly and incorporate into my writing as best I can. Are my words in that "download space" 100% magnificent words, needing no editing? Nope. I still have to edit and flesh them out, massage some words and cut deeply into others. But that isn't the point. The point is that I've found a way to court the story back and we can dance together for a few days before I have to return to my day-to-day life where the story must take a back seat to my family and work. I used to be afraid that the story would leave me. But I'm not now, because I've also discovered what the true meaning of a "ritual" is. It isn't some dead by-product of a religion that has no meaning in my life (what I used to think of rituals as being), but rather a way to court the Mundus Imaginalis to my side, to entice the stories to walk with me. Rituals are a way to heighten our awareness of the more-than-human world this is alive and talking to us. This is not a metaphor. Thanks to Terrence McKenna for saying it so plainly. |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed