|

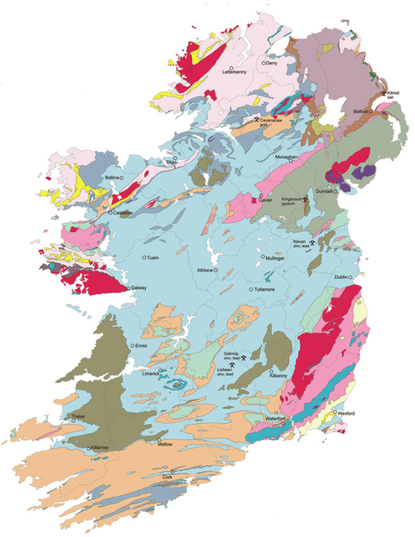

It took me a long time to settle on a title for this book. When the story first presented itself to me, the word "Dawnland" kept coming into my awareness, and I thought that was to be the title. For a long time, I called it "Dawnland" until I discovered that "Dawnland" was the English translation of the the traditional name of Abenaki territory - Wabanahkik -- and that the use of that word outside of that context was cultural appropriation. I am working hard to make sure that my portrayal of First Nations people in my books be respectful. I have no wish to appropriate wisdom and teachings that are not mine to use, so I abandoned "Dawnland" as a possible title. I came to the idea for the title The Other Land when reading about Irish descriptions of a mythical "tribe" who came to Ireland in the distant, misty past. This tribe was called Tuatha de Danann (pronounced "thuey de du-non), which translates as "the tribe/kin of the goddess Danu/Anu." Danu/Anu was the mother of the Irish gods and members of this tribe/kin group are many of the gods and goddesses that are worshipped by the pre-Christian Irish, including the triad of goddesses often called the Morrigan (Mor-EE-gan), who may actually be another name for the great goddess Danu/Anu. Textual references to this very ancient goddess are unclear and have been corrupted by the intrusion of Christian philosophical overlay, so we can say very little with conviction on the topic. The place of origin for the Tuatha de Danann is similarly murky. The tuath arrived on the island of Ireland by ships over the Western Sea (the Atlantic) and then burned their ships upon arrival. Where did they come from? The stories indicate many things, most of which -- rather inconveniently -- conflict with each other. This land was said to have been an island to the north and west. OR this land could have been accessed by the Bronze Age burial mounds known as the sidhe (shee), already ancient when the Celtic peoples came to Ireland. OR this land was overlaid onto ours in some mysterious way and could be accessed by deep woods, groves of trees, lakes and pools of water, wells, and thick mist. There they would have met gods, or fairies, or mythical animals. It was considered to be a supernatural realm of wondrous technology and eternal youth, a place where heroes and mortals might find themselves lost for many years, only to return with the world changed forever. The names for this original "homeland" for the Tuatha de Danann were varied. Sometimes parts of the this mystical realm were referenced by a specific location within the land, indicating a kind of inner-geography. In Gaelic, the more general names are: Tír nAill (The Other Land), Tir na nÓg ("The Land of the Young"), Tír Tairngire ("Land of Promise"), Tír na mBeo ("Land of the Living"), Emain Ablach ("The Isle of Apples"), and Tír fo Thuinn ("Land under the Wave"). Specific places within this mythical land are: Mag Mell ("The Plain of Delight"), Mag Findargat ("The White-silver Plain"), Mag Argatnél ("The Silver-cloud Plain"), Mag Ildathach ("The Multicoloured Plain"), Mag Cíuin ("The Gentle Plain"). There is also an additional otherworldly realm called Tech Duinn ("The House of Donn/The Dark One"); this land is sometimes identified as an island toward which the souls of the dead departed westwards, to the land closest to the setting sun, over the western sea. Ireland's geography is that (generally) of an upland, fertile plain surrounded by mountains along the coast in every direction. When the Irish poets described the Other World to their audience as a "Plain of Delight," or "The Multicolored Plain," they were describing a very familiar inner-space of a landscape much like their own. This is the "long story" about why my book has the title it has. Just in case you were wondering. If you wish to know more about the subject, and there is a great deal to learn (and I'm still learning), I recommend the following: Take Sharon Blackie's Celtic Studies course (there is a new intake happening this April). Sharon Paice Macleod's book Celtic Cosmology and the Otherworld is fantastic, and a great resource on the Otherworld specifically. Also, Mark Williams' Ireland's Immortals is a thorough book that has a historiographical bent (which is refreshing), although I think he gives the Morrigan short shrift... (but that's just my personal bias.) -- Marie Goodwin

2 Comments

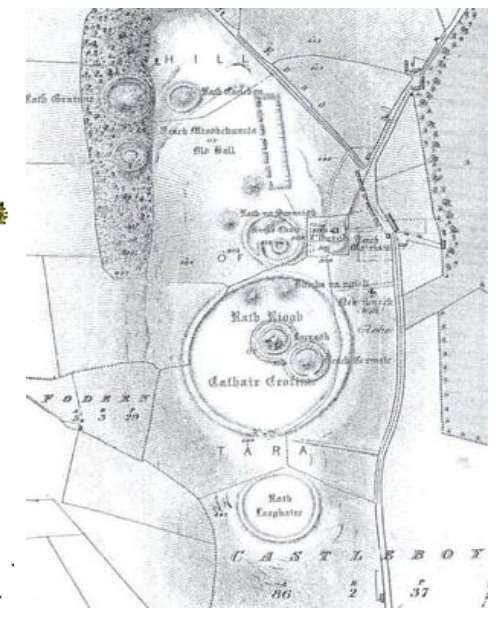

Photo: Anthony Murphy (Mythical Ireland). The Battle of Tara took place in the open fields surrounding this hill. I briefly mentioned The Battle of Tara in my last blog post, and I thought I might want to expand upon the importance of it a bit. It took me months of reading, re-reading, creating family trees in a notebook, and developing a detailed chronology to understand the political maneuvering that took place during this time period, and I have a new-found respect for any historian working in medieval Ireland. Kudos to you... This battle was an important turning point in the power relationship between the Irish and the Foreigners (the Irish name for the Vikings). For two hundred years, the Vikings pillaged up and down the river systems in Ireland and along the coasts as well. They established cities and controlled their important trade markets. (Dublin was founded by Vikings, as was Limerick and Waterford.) They settled in numbers around those cities as well, and owned land and intermarried with local families, both royal and common. The Foreigners took untold numbers of Irish women and girls and sold them into slavery throughout the Viking world. And they inserted themselves into the chaotic and complex political world of competing kingships and regional alliances. Hundreds of Irish kings held large and small tuaths (kingdoms) in Ireland at the time, and the kaleidoscope of ever-shifting alliances, competition, and enmity with each other during this period did not allow for a unified defense by the Irish against these Foreigners. Not until the Battle of Tara. The lead up to the battle was complex. There were two key players: Máel Sechnaill (pronounced "mell sheknal") and Olaf Cuaran. Máel Sechnaill was a young king (31) of Mide (the area to the center of the island, north east of Dublin). He had only been king for a few years when the long-time high king Domnall uí Níall (Máel Sechnaill's uncle) abdicated and went to a monastery at Armagh to live out his days (he died shortly after). Máel Sechnaill was from a royal line of the Uí Néill dynasty (ruling northern Ireland) who had, for some time, dominated the title of Ard Ri -- the High Kingship -- with its seat at the Hill of Tara. He wasn't untested in battle, but he was relatively inexperienced. Relative to the Viking king Olaf Cuarán that is. Olaf Cuarán was the Foreign king of Dublin. He was also Máel Sechnaill's step-father. At 53, he had been involved in Irish political life for many years. He made alliances through two marriages, and saw both of those alliances fall apart. His first wife Dunflaith was the sister of Domnall uí Níall (see above) and Máel Sechnaill's mother (by a previous marriage), but that did not secure peace between the north, Mide, and Dublin. In fact, Domnall and Olaf fought bitterly for many years, brothers-in-law, and late in the the 970's Olaf Cuaran murdered Domnall's two adult male children and heirs in a wedding procession. When Dunflaith died, probably in childbirth, Olaf married Gormflaith, daughter of Murchad mac Finn, another regional king. Gormflaith was a teenager at the time of their marriage, but widely considered to be the most beautiful woman in Ireland. She bore him at least two children, perhaps three, by the time of the Battle of Tara. Her relatives proved to be unruly and combative against Olaf's interests as well, and the alliances between their families fell apart almost as soon as the marriage was made. Olaf's ire was not only directed at his brother-in-law. He spent much of the 970's harassing and battling with other kings in Leinster (central/eastern Ireland) and Mide, vying for better trade advantages and access to land and power. He had a long history of capturing enemy royal family members, ransoming them off (if they were lucky) or killing them. A few months before the Battle of Tara, Olaf Cuarán captured the Leinster king Domnall Claen. He also captured Domnall's son Broen when Broen attempted to rescue his father. This capture was made even more interesting because Domnall Claen was Gormflaith's father's murderer. Domnal Claen was said to have killed Murchad in cold blood (not in battle) in some sort of vengeful rage about which we have no details. Gormflaith had to have been quite happy that her husband held her father's murderer as a prisoner. To me, it seems likely that she may have had a hand in it. I will do a whole other post on Gormflaith later. But for now I will say that I am quite sure she was not just sitting in her room weaving while all of the intrigue swirled around her. Both sides knew that this kidnapping of the Domnall Claen meant war, but the Leinster leaders could not openly amass an army for fear that their King would be killed. In secret, they gathered an army of allies -- an unprecedented alliance in such a fractured political arena -- north of the city. Olaf must have not known this was happening, because he didn't kill Domnall or Broen in retribution. But Olaf had his own plans. He must have sensed that the Irish were plotting or that he had an advantage, so he amassed an army by calling in allies in the Hebrides and Orkneys and snuck the men into Dublin, probably on merchant ships. In June of 980, both sides readied their armies and met near the Hill of Tara, about a day's ride north-west of Dublin. This hill was the traditional and mythical seat of Irish kingship, and so the choice of location was purposeful and symbolic, probably Máel Sechnaill's decision. At the end of the day, the Viking army was routed. The annals describe it as being a bloodbath. Olaf's son Ragnall (the lead commander) was killed. Máel Sechnaill then surrounded Dublin and took control of it, freed the all of the slaves, and then pillaged all of the amassed wealth in the city and burned much of it to the ground. Domnall Claen managed to survive, but Olaf had killed his son Broen in the lead up to the battle. Olaf was sent to a monastery in Iona and died soon after. Gormflaith married Máel Sechnaill and he took in and raised her children with Olaf and they had children of their own. Máel Sechnaill was now Ard Ri -- the High King of Ireland. But not for long, because Brian Boru, a powerful king in the south of the island, had other ideas about who should have that title. Even though the much more famous Battle of Clontarf (in 1014) has been traditionally seen as the final downfall of Viking power in Ireland, it was really the Battle of Tara that brought it to a close. --Marie Goodwin From left to right: A computer recreation The Hill of Tara; A map of the battle's location; a map of the entire complex of structures on The Hill of Tara

Image by Patricia Ariel entitled "Compassion." I knew a few things about my character Una when I began writing The Other Land: that she was born about 960 and that she was caught in the political intrigue leading up to the Battle of Tara (June, 980). I also knew that she was a Bandrui, a female druid, the last of her line in a hereditary tradition of Bandrui. I also knew that Christianity had all but eliminated her Bandrui lineage in Ireland. Indeed, the time period of my book represented the very last of this long-standing indigenous religious tradition. I knew that it would have been a shadow of what it had once been, changed utterly from the time six hundred years before when the Druidic powers were ascendant in Ireland.

But what of the Bandrui? Who were these women in Ireland? What were their traditions? I wanted to show that these women in my book came from a long and proud line of woman who could heal the sick, birth babies, foretell the future, interpret dreams, throw lots, act as conduits for prophecy, shape-shift, and were conduits for communication between the human realm and the natural world. But what would this look like in a world where the teachings of the Church instructed people to be suspicious of such women? What was the social standing of these women in their local community? How would they interact as political players? (We know that, historically, both Druids and Bandrui were deeply involved in the political sphere of influence at play in Ireland, which was complex and ever-shifting.) What did their everyday life look like as they stood on the cusp of the annihilation of their lineage and their training? When I began to research these questions, I realized that there is so much we cannot know about the indigenous, pre-Christian religious tradition in Ireland, especially when you begin to ask about women's roles in this tradition. I was confronted with this reality almost immediately when I started to research the book. There is an abundance of textual evidence that the Bandrui lived and thrived in the earlier part of the first millennium in Ireland. For instance, we see Fedelm in the Táin Bó Cúailnge; Bodhmall in the Fenian Cycle; Bé Chuille, Dub and Gaine in the Metrical Dindshenchas; Relbeo from the Book of Invasions; Eirge, Eang, and Banbhuana are bandrui in the Siege of Knocklong; and of course Tlachtga, the daughter of the great blind Druid Mug Ruith, in the Lebor Gebála Érenn. These are only a sampling, and there are many, many more tales that come down to us from not only Ireland, but Scotland, Brittany, and the Celtic mainland as well. The Romans, complicated witnesses though they were on these matters, were fascinated with these women. But did they even exist in the years leading up to the Battle of Tara? That is 600-1000 years away from these earlier tales and come after the cultural disruption and overlay of Christian thought and power. What evidence is there for Bandrui approaching the turn of the first millennium? Let me begin by saying that the evidence for women's lives, in general, during this period of the middle ages is often circumstantial no matter what area of interest you are trying to investigate. Archaeological evidence for women's lives is ephemeral at best. Of course, we know that women lived and died, and raised families and tended to the economy of the household in a myriad of ways. But what do the texts of the period say? To begin with, very few texts dating back to 980 exist. Most of the texts we have pertaining to this time period are copies of copies of copies, written and re-written by male Christian monks in monasteries. These monks were people, with biases and causes to advance, like any person writing today. This means that some ideas and traditions were illuminated (some quite literally, with gorgeous paintings on the parchment) and brought forward in time by copying. Some were, sadly, discounted and not copied. Stories of powerful females in a pre-Christian world were unlikely to be thought important, and so many of them are now lost to us because of this erosion of the oral and written tradition. But yet, some evidence remains. And this is where Max Dashu comes in with her unbelievably important work Witches and Pagans: Women in Indigenous European Folk Religion: 700-1100. Seriously... if you are interested in this topic at all, order this book. This book saved me years (and that is no exaggeration) of research. There IS evidence of how women were involved in folk religion around the turn of the first millennium. In fact, there is enough to fill a book. First of all, these women had many names that are mentioned in medieval texts: (fyi: "ban" = woman, "cailleach" = old woman) Bandrui, banfili (highly skilled and initiated female poet), banfissid (seer), ban feasa or cailleach feassa (woman of special healing and symbolic knowledge); ban leighis (medicine woman); banthuathaid (woman of the north), calleach phiseogach (an old woman who uses charms). These texts that mention these women include dozens of stories, law texts, Christian religious texts (often admonishing lay people to stop using the services that these women provided). The Annal texts from Ireland sometimes mention the death of these women. In fact, one such woman is mentioned in my book: the Ollamh Banfili Uallach daughter of Muinechán, who died in 934 and is recorded "the woman poet of Ireland" in the Annals of Innisfallen. These women are associated in texts of this period with many skills: powers of prophecy, divination, incantation, healing, herbal knowledge, shapeshifting, shamanic flight, dream interpretation; they carried magical staffs, wore masks, and often had associated animal spirits. The language used to describe them ties them to various kinds of wisdom, but also the ability to dictate and change one's fate. Texts also suggest that they took part in some sort of an initiatory process into (poorly understood and basically unknown) religious mysteries. Although the bandrui are not mentioned by name, the legal texts (The Brehon Laws) of this time-period indicate that some very unusual women (who had special skills, usually unspecified in the law) were honored as cultural authorities and granted power, land, and independence from male oversight (in many cases). There were legal statutes that mention women of special standing retaining power and property in marriage as well as the right to pass down property to daughters. The laws make it clear, however, that this was rare and special to only certain women of power. The Brehon Laws also describe penalties for banfili who make fun of powerful men in public, thereby dishonoring them. (This was not just a "saving face" issue, but rather a legal problem in Ireland, where your honor was tied to your legal standing.) The Brehon Laws were the "law of the land" from very early in the first millennium. They were first written down in the 7th century, but were primarily an oral tradition and their origins date back to an unknown (and unknowable) pre-literate distant past. They Brehon laws were still used in some parts of Ireland until the 17th century, although their universal and customary use was under great pressure from the English legal systems from the late 12th century onward when the Anglo-Normans invaded Ireland and never left. (To read more on the Brehon Laws, I quite enjoyed The Lost Laws of Ireland, by Catherine Duggan.) One last bit of evidence comes from rituals in Ireland surrounding kingship. In a fascinating book -- Lady with the Mead Cup by Michael Enright -- we learn of the roles woman enacted in rituals when kings were "made" by their kin-groups. (Kingship was not hereditary, but held within kin groups, so new kings were chosen.) Christianity inserted itself significantly into these rituals by the turn of the millennium, but the texts indicate that special women, invested with the some type of atypical power, were involved in rituals of kingship in very specific ways deep into the middle ages. These women were symbols of the new king's marriage to the land over which he was to be sovereign. Who were these women? We know very little about them, other than the fact that they were there. So in my book, The Other Land, I've used the tradition of the Bandrui and fused them with the the kingship rituals of "sovereignty" that fill the old Irish tales to make for an even more interesting tale. So, the evidence that exists for Bandrui is ephemeral and suggestive, rather than definitive. But there is an echo, a breath, a wisp of a "maybe" that they were still active, that they lived and died and worked in relative obscurity even as late as 1000 AD. My depiction of the bandrui in The Other Land is fiction, but it is an attempt to read between the lines of these old texts and breathe life into the woman who wove together the living fabric of those around them, in ways seen and unseen by history. - By Marie Goodwin |

|

© COPYRIGHT 2019. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed